Subject: beylerbey commander of sipahi knights

Culture: Ottoman Turk

Setting: imperial warfare, Ottoman empire 16-17thc

Caveat

Context (Event Photos, Primary Sources, Secondary Sources, Field Notes)

* Tallett/Trim eds. 2010 p114-115 (Gábor Ágoston, "Ottoman-Habsburg rivalry and military transformation," p110-134)

"The early sixteenth-century Ottoman military was considered by European contemporaries to be the best and most efficient in the world. The bulk of the Ottoman army consisted of the fief-based provincial cavalry (timar-holding or timariot sipahi), whose remuneration was secured through military fiefs or prebends (timar). In return for the right to collect well-prescribed revenues from the assigned timar lands, the Ottoman provincial cavalryman was obliged to provide for his arms, armour, and horse, and to report for military service along with his armed retainer(s) when called upon by the sultan. The number of armed retainers whom the provincial cavalryman had to keep, arm, and bring with him on campaigns increased proportionately to his income from his fief. From perhaps as early as the reign of Bayezid I (r. 1389-1402), muster rolls were checked during campaigns against registers of timar lands in order to determine if all the cavalrymen from a given region had reported for military duty and brought the required numbers of retainers and equipment. If the cavarlyman did not report for service or failed to bring with him the required number of retainers, he lost his military fief, which was then assigned to someone else. The timar fiefs and the related bureaucratic surveillance system provided the Ottoman sultans through the late sixteenth century with a large standing cavalry army, while relieving the central Ottoman bureaucracy of the burden of revenue raising and paying military salaries. In 1525 there were 10,668 timar-holding sipahis in the European side of the Empire, and 17,200 in Asia Minor, Aleppo, and Damascus. Based on their income, they were capable of providing at least 22,000 to 23,000 armed retainers, although some estimate the number of possible retainers at as high as 61,000. In sum, the total potential force of the standing provincial cavalry can be estimated at a minimum of 50,000 men (and perhaps as many as 90,000 men)."

* Arnold 2001 p120-121

"The sultan's artillery and janissaries were both impressive, but the real soul of Süleyman's army resided in the cavalry. Like the noble's of the West, the Ottoman political and military aristocracy was a horse culture. The Turkish horseman of the fifteenth and sixteenth century had given up some of the more curious details of his nomadic heritage -- such as a kind of lariat used to entangle the legs of an enemy horse -- but the deeper spirit of the steppe lived on. Fighting was the province of warriors, and a combination of horsemanship and athletic skill at arms (especially archery) was the quintessence of being a warrior. Ottoman cavalry, both Turkish and other ethnic types, understood discipline in the sense of courage and devotion, but not in the sense of sophisticated formal tactics. This was not necessarily a detriment. After all, Eastern horse, in the form of stradiots, hussars and others, were in high demand in the armies of the West. But these light horse were a small proportion of any Venetian, French or Spanish army, and they were supplementary hirelings -- not the core and political élite. Turkish noble cavalry, the spahis, took the field in enormous numbers, and were usually the largest portion of the regular field army. (There were always large swarms of irregular horse and foot as well.)

"The spahis were not just the core of the sultan's army, they were also representatives and products of one of the defining institutions of the Ottoman Empire, the timar system. Each horseman was supported by a particular piece of land, a timar, which was not a fief but a gift for life from the sultan. The spahi's equipment depended on the quality of that holding. Probably only the wealthiest had complete suits of mail armour, reinforced with attached plates; most had only a helmet and a mail shirt. Their horses, though light in comparison with those of a western man-at-arms or pistoleer, were excellent. The weapons of choice remained the light lance, the scimitar and, above all, the bow. Again, we have evidence of cultural resistance to change. Like many a Christian prince, Süleyman was personally fascinated by pistols, as were other well-placed Ottomans. According to a Habsburg ambassador, at mid sixteenth century a Turkish prince attempted to rearm his personal retinue with firearms, but the horsemen refused to have anything to do with the weapons and so the attempted innovation, fascinatingly similar to contemporary cavalry experiments in western Europe, was a failure. Aristocratic distaste for firearms was also present in the West, but there it was a minority and reactionary sentiment. This was not so in Ottoman lands, where janissary slave soldiers adopted the new weapons, but the landed nobility remained aloof."

* Bennett 1998 p297

"spahi Ottoman word for a heavily armoured cavalryman, either raised from the provinces supported by a timar estate or supported in the sultan's bodyguard."

* Vuksic/Grbasic 1993 p112

"Sipahis were the mainstay of the provincial army (elayet), and the most numerous of the Ottoman armed forces; there were about 40,000 of them in the sixteenth century. Their units were called alay, each with 1,000 men, and they were commanded by an alay-bey, who reviewed his sipahis before going to war according to a register (defter) of feudal holdings. Every tenth sipahi remained at home to keep the peace and do the work of those who had gone to war."

* Rosenthal/Jones 2008 p447 (Cesare Vecellio, writing in 1590)

"Nothing about the Turks causes such wonder as the speed of these Beglierbei in warfare, for they are quick to face danger and to obey their commanders, especially their Lord. They swim across deep rivers, make their way over steep mountains, and march through difficult terrain, risking their lives in obedience to him. They endure sleeplessness, hunger and thirst exceptionally well, and in battle they emit quavering shouts rather than any other cry. At night they maintain such silence in their quarters that, if need be, they would rather let prisoners escape than make any noise in the camp. It is claimed that they fight with greater military strategy than any other nation. So it is no wonder that the empire of the Turks increases every day, and it can be truthfully said that this nation has been undefeated for almost two hundred years. No soldier rides armed but has his weapons and baggage carried behind him. Instead of banners they carry lances with variously colored threads hanging from them, which identify the captains." ...

* Nicolle/McBride 1993 p7

"Although the highly disciplined Janissaries most impressed the Europeans, their importance was far less than that of the sipahi cavalry, the battle-winning offensive element in a classical Ottoman army. The Janissaries were also trained to attack, but they did so at a rush in large closely-packed formations which rendered their gunfire largely ineffective."

Armor (Helmet, Cuirass)

* Gorelik 1995 p37

"The armoured Turkish knights, the spahi, wore mail-coats and cuirasses, combined mail-lamellar armour, either pointed or low helmets, brassards and greaves. They were equipped with sandaks, sabres, broadswords, daggers, knives, battle-axes and spears, and rode barded horses."

* Robinson 1967 p66-67

"The late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries are richly represented by armours commonly termed 'janissary', after the famous Turkish infantry, which were acquired in quantity from St. Irene in the last century and dispersed throughout Europe.

"[...] The so-called 'janissary' armours were, however, for the cavalry (spahis) and consisted of large circular convex plates for breast and back, with a series of plates attached with mail for the shoulders and neck, the chest, and sides of the body. They were decorated with radiating flutes and embossed and engraved ornament and the edges were always trimmed with silk fringes. ... [Sixteenth-century helmets] are of tall, conical, crowned type and in most cases fluted.

"The Turkish mail and plate cuirasses (korazin) were completed with bazuband or vambraces and worn over a mail shirt -- and not infrequently with complete leg armour, consisting of small plates and mail for the thighs with circular knee-plates, splint and mail greaves for the lower leg, and mail or mail and plate shoes."

* Vuksic/Grbasic 1993 p24

"[T]he rich spahis had armour for themselves and their horses. This was of Persian design, but Ottoman made, and consisted of steel plates of varying sizes connected by mail, forming an exceptionally flexible armour (korazin). Other types in use included scale (pirahen ahenin), lamellar (cukal), lamellar cuirass (cevsen), mail coif (zirh), mail hauberk (air kulah), vambraces (kolluk), round shields (kalkan), helmets (cicak) and a round metal plate for head protection which formed part of the mail hauberk."

Saber

* Seitz 1981 p348

"Kilij (Kilîdsch) ist die Benennung des des typischen türkischen Säbels, dessen Klinge etwas breiter ist als des persischen shamshir, er ist auch nicht so stark gebogen wie jener und hat eine verbreiterte, zweischneidige Spitzenpartie, Jelmán. Trotz der 93,5 cm langen Klinge beim ersteren der beiden angeführten Exemplare, beträgt die Pfeilhöhe lediglich 7 cm."

* Atıl 1987 p147-148

"The Ottoman sword, renowned for the elasticity and strength of its blade, was highly prized. The type called kiliç is slightly curved and has a unique blade that widens on the cutting edge two-thirds of the way toward the tip and forms a spur, thus concentrating weight of the weapon at its lower portion and increasing the effectiveness of the blow. The kiliç demanded agile wrist action rather than strength in the arm. Extensive training was required to achieve the proper technique. The shape of the blade, which became characteristic of Ottoman swords, appeared during the reign of Mehmed II, coexisting with the classical straight sword. Its distinctive curve evolved during the first quarter of the sixteenth century, achieving the perfect balance between weight, length, and shape during the reign of Süleyman.

"Süleyman's functional swords, made for use in the battlefield and on hunting expeditions, have flattened and slightly tilted hilts, which are generally covered with leather to provide a good grip. The pommels and guards are frequently made of silver, at times gilded and inlaid with niello; in some examples these components are of blackened steel decorated with gold, employing a particular technique called küftgari, in which gold wire was hammered onto the roughened steel, resembling overlaying. The matching scabbards, covered with leather similar to the hilts, have silver or steel chapes, lockets, and sling mounts used for attaching the weapons to belts and decorated in the same manner as the pommels and guards. Some of the mid-sixteenth-century examples were also embellished with jeweled plaques. The steel blades are inlaid or overlaid with gold and at times embellished with gems. Many examples contain the figure of a fish placed on the hilt, which appears to be a talismanic symbol; its proper meaning is yet to be understood."

* Calizzano 1989 p90-92

"Le Kilij "Déjà utilisé vers 1500 dans les pays soumis à l'influence ottomane, il fut probablement l'arme qui diffusa la conception du sabre dans l'immense territoire de l'empire musulman.

"La lame est en acier damas; le côtés, tout d'abord parallèles, devienent légèrement convergents à mi-distance, créant ainsi un rétrécissement de la largeur. C'est là que prend naissance une courbure assez prononcée, la lame s'élargissant simultanément pour former le yelman. Le fil, s'étendant sur l'ensemble de la partie convexe, tourne autour de la pointe et se prolonge sur environ un tiers du dos, occupant pratiquement tout la longueur du yelman. Le plat de la lame peut être enrichi de décorations ou de versets du Coran.

"La poignée, en métal, ivoire ou corne, se termine par un gos pommeau dirigé vers le tranchant de l'arme et comportant un trou réservé au passage de la dragonne. La garde est presque toujours en croix droite, avec des écussons au milieu qui retiennent soit le fourreau, soit la poignée. Comme tous les sabres, cette arme possède un centre de gravité très déporté vers la pointe, témoin de sa prédelection pour les coups de taille."

* North 1985 p27-28

"By the 16th century the curvature of the blade had increased and the pommel cap was set at a definite right angle to the grip. This basic shape, with slight variations, remained in use until the 19th century. At some point in the latter part of the 16th century blades were formed with a substantial flat back, and developed a graceful curve.

"At some time in the 17th century there was a tendency for the pommel and grip to be made in one, usually of horn or wood. Grips were made of a variety of materials, horn, wood and precious metal were all used; some swords were mounted with Mogul jade hilts."

Mace

* Aydın 2020 p164

"Mace (topuz) is a type of weapon that is used in close combat. It is called as such because of its round head. It is generally made of a head called 'topuz' and a handle adjacent to it. Maces can be made from one piece iron or copper masses as well as from wood for the handles and iron or copper for the head.

"Mace is 'bozdoğan' in Turkish. The maces were generally used by cavaliers and infantry. Cavaliers had heavy maces while the infantry had light ones. The cavaliers hung the maces to the left of their saddles."

* North 1985 p40-41

"The mace with a head formed of flanges was widely used in Islam. In Turkey the head is often set with a large number of flanges, put closely together and usually fitted with a comparatively short shaft."

* Rogers/Ward 1988 p144

"Maces are shown carried by senior officers in war and on the hunt, and by Süleyman himself in illustrations to the Süleymānnāme. They were also ceremonial, and bejewelled maces ... must have been primarily for show."

* Atıl 1987 p148

"Ottoman maces, with gold-sheathed iron, rock-crystal, or jade heads, were beautifully fashioned, either simply carved or embellished with gems. These decorative pieces were also formidable weapons, their elegant shapes and surface embellishment belying their deadly purpose."

* Atıl 1987 p151

"Ottoman maces were also made of rock crystal, jade, and silver; some have spherical or flanged heads, others show balls attached to chains."

Shield

* Atıl 1987 p148

"The most decorative and yet extremely functional Ottoman battle accoutrements were wicker shields, embroidered with silk as well as silver and gold threads, lined with velvet and padded, and supplied with steel bosses, frequently decorated with gold inlays and gems. Their laborious technique involved wrapping long strands of twigs with silk and metal threads and stitching them into place to form the shields. Wicker, an extremely strong and resilient material, was also lightweight, an asset for cavalrymen and foot soldiers alike. Similar shields appear to have been used in India and Iran. Although extant Indian examples have not been published, warriors carrying shields with concentric lines, obviously representing wound wicker, are depicted in late-sixteenth-century Mughal manuscripts. A few Iranian examples have survived, the most interesting of which is decorated with a series of lions attacking bulls."

* Rogers/Ward 1988 p152

"[D]ecorated shields appear in battle scenes in illustrated manuscripts of the Timurid, Akkoyunlu, Safavid and Ottoman periods. Despite their flimsy appearance they were highly effective: the central boss would cause arrows to glance off, while the wicker was the only efficient way of stopping direct hits from the composite bow which could pierce steel and which for most of the sixteenth century remained a far more efficient weapon than firearms."

* Atıl 1987 p160

"Among the most decorative and yet functional arms and armor were embroidered wicker shields, which must have created a dazzling spectacle when the army marched to battle or paraded through cities. These extremely sturdy and lightweight shields have basically the same shape and size; they are 60 to 67 centimeters (about 23 to 26 inches) in diameter, with a slightly convex outer zone constructed of wound wicker. The central boss, rising to 15 or 16 centimeters (approximately 5 inches), was made of steel or iron and often inlaid with gold. The underside is padded and lined with velvet or other soft fabrics, has a square cushion in the center to protect the elbow, and is supplied with cord handles and fastenings that looped around the arm. The designs on the wicker portion are varied, combining saz scrolls, sprays of naturalistic flowers, cloud bands, and

çintemani patterns.

"Wicker shields, which appear to have been introduced in the first half of the sixteenth century, were used throughout the 1600s. There is little evidence that the practice continued beyond the eighteenth century; changes in warfare technology may have made them obsolete."

Sword

* Atıl 1987 p148

"[A type of sword called meç shaped like a skewer] which dates to the reign of Mehmed II, was produced in limited numbers and obviously functioned more as a piercing instrument than a cutting one, possibly to penetrate armor."

* Аствацатурян 2002 p102

"Meнee pacпpocтpaнeннын, чeм caбли, opyжeм в Ocмaнcкoй импepии XVI-XVII вeкoв были пaлaши.

"Пoльзyяcь тeми жe пpизнaкaми, чтo и для caбeль, пaлaши мoжнo дaтиpoвaть XVI и XVII вeкaми; зти пpизнaки -- opнaмeнтикa и фopмa pyкoяти."

Dagger

* Atıl 1987 p148

"Süleyman was hardly ever represented wearing a dagger, even though a number of these weapons were produced during his reign. Some of the daggers have carved rock-crystal and ivory hilts, while other hilts are made of jade or ivory inlaid with gold and set with gems. Most of these daggers appear to have been made as gifts or display pieces and were not an integral part of the sultans' outfit as they were in Iran or India."

* Atıl 1987 p157-158

"Imperial Ottoman daggers ... appear to have been more decorative than ceremonial or functional, and were frequently presented as gifts. For instance, during bayram celebrations the sultan received daggers or dagger handles from goldsmiths, gold inlayers, gemstone carvers, and the members of the kündekari society. He must have also sent daggers as diplomatic gifts to neighboring states, for some superb examples are housed in European royal collections.

"Most of the Ottoman daggers have a straight double-edged blade with a pierced central groove and are inlaid with swelling sides and a lobed pommel; they are made of ivory, mother-of-pearl, jade, or other precious materials, often inlaid with gold and set with gems. Some daggers have matching scabbards, employing the same materials and designs as those used on the hilt. There are also several daggers with slightly curving blades or cylindrical hilts."

* Treasures of Islam 1985 p306 (David Alexander & Howard Ricketts, "Arms and Armour" p294-317)

"Turkish ivory hilts of this type seem to date from the middle of the 16th century onwards for about fifty or sixty years."

Archery

* Mártin 1980 p74-76

"Las armas tradicionales turcas, el sable y el arco, tampoco podían compararse con las occidentales. Especialmente el arco -- cuya construcción, a base de madera, cuerno, tendón y colapez, requería un año entero, pero que, así fabricado, tenía utilidad durante cien años -- era de altísima calidad. El arco flexible turco era superior al sencillo arco europeo tanto en alcance (800 metros, tiros certeros a 300 y 350 metros) como en estabilidad. Los arqueros turcos estaban entrenados para utilizarlo en caulquier situación bélica. Lanzaban sus flechas al galope, incluso en retirada, por encima del hombro, sin por ello reducir demasiado su puntería. Además, disparaban en forma de salvas."

* Rogers/Ward 1988 p152

"Archers' thumb-rings were for the thumb of the right hand, to enable the archer to make a cleaner shot with the bow, allowing the maximum force behind the arrow. When released, the string would slide smoothly off the jade surface, with minimal friction. Archers' thumb rings have a long history, but some of the most elaborate and finely decorated were produced for the Ottoman court. They were as much for show as function, and were worn or hung from the belt during ceremonial occasions. Tavernier mentions that they could also be used when executing disgraced officials to tighten a handkerchief wound round the throat." [reference omitted]

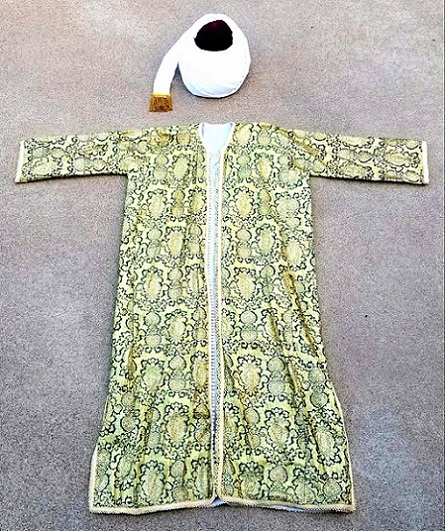

Costume

* Rogers/Ward 1988 p165

"The Ottomans were fairly conservative in the tailoring of their dress: it was the quality of the material which was intended to impress, although the majority of surviving caftans are of plain material .... They were usually cut straight, or slightly tailored to the waist, flaring out over the hips and then more gradually down to the hem. They generally have round necks, sometimes with a small stand-up collar. Usually they have buttons down to the waist, either jewelled or covered in the same fabric as the caftan and fastened through loops, and often frogging in a similar material across the chest."

Bottle

*

"

Bard/Tack

*

"