Subject: koroi 'killer'

Culture: Fijian

Setting: tribal warfare, Fiji late 18th-mid 19thc

Evolution:

Context (Event Photos, Primary Sources, Secondary Sources, Field Notes)

* Meyer 1995 v2 p458

"Fijian society was based on chiefdoms, with each larger tribe made up of sub-groups, the smallest being the extended family. Chiefs took office either on hereditary grounds or as a result of military achievement."

* Waterhouse 1997 p298 (writing in 1866, describing the investiture of knights)

"This ceremony is repeated, with slight variations, on every occasion that an enemy is slain and a new name given. Many thus receive four names of knighthood. To each name of a knight of the single order is prefixed the significant Koroi."

* Meyer 1995 v2 p462

"The Fijian social and economic system thrived on war, which always began with a very civilized ceremony called tatau -- a way of saying goodbye to the enemy. The scope of Fijian warfare is clearly demonstrated by the military review (taqa) staged in 1846 at Somosomo for the famous high chief Cakobau, later king of all Fiji. It involved the presentation of 40,000 yams, a solid wall of yaqona root measuring 3.5 meters high and 11 meters long, and 20 bales of tapa cloth; 200 warriors dressed in ceremonial tapa were seated in attendance. After much ceremony, an army of 3,000 men, organized into companies by weapon-type, paraded in front of the king. Battles are recorded with over 15,000 warriors in the field at the same time. The Fijians often practiced >>scorched-earth<< tactics, systematically wiping out an entire enemy group. Those enemies who were spared immediate death were kept alive as food for a rainy day."

* Archey 1967 p68-69

"In warfare the Fijian laid his plans carefully, and exploited an artful diplomacy to foment discord among his enemies and fasten allies to his own side. For all that he was heavily armed, he employed stratagem and skirmish rather than direct attack. The favourite wile was 'the net': the attackers broke and fled, leading their heedless pursuers into ambushes -- a simple ruse, that succeeded surprisingly often.

"Although fighting was constant in the early days, the aggregation of tribes by conquest and alliance did not produce large federation until European times, when the early acquisition of muskets gave the district of Mbau an initial advantage. But as other tribes became armed and effected other alliances, a long period of almost universal war and rebellion ensued. The final supremacy of Thakombau, or Mbau, was the result of his enlisting the aid of Tongans, who, having long harried the coasts of Fiji in the manner of the Scandinavian [V]ikings, had become firmly established in the Lakemba group, or 'windward islands,' which lie some 200 miles to the eastward."

* Arts of the South Seas 1946 p17-18

"The Fijians are, perhaps, best known to Europeans for their warlike habits and for the practice of cannibalism. Fijian tribes were at war most of the time, but they were not a particularly courageous people and the casualty lists were small. To paraphrase a well known verse: They went forth to battle but they usually ran away. A measure of their ferocity can be found in their weapons; huge clubs of fantastic form and elaborate decoration and many barbed spears of unwieldy length which seem to have been designed quite as much to reassure their bearers as to injure the enemy. The importance of cannibalism in the native culture was considerably overrated by early writers. After a battle, the victorious party would eat the bodies of their slain enemies. Captives might also be killed and eaten while blood was hot and there was an unpleasant Fijian rule that all castaways went into the pot, but even enemy tribes were not hunted for meat. Cannibalism seems to have been inspired partly by motives of revenge, partly by the wide-spread idea that it was an effective means of acquiring an enemy's desirable qualities. Human flesh was taboo to women and even men used forks in eating it so that they would not have to touch it directly with their hands."

* Derrick 1950 p48

"In the new type of warfare which resulted from the introduction of firearms and the growth of powerful kingdoms, there was still little bloodshed in actual fighting, except when villages were destroyed with all their people. As in warfare of the old style, the losses were highest among the common people, who continued to be waylaid, ambushed, clubbed, and eaten, in the best tradition.

"In the miscellaneous character of its weapons, a Fijian army must have resembled the peasant rabbles of European history, with their bill-hooks, scythes, pitchforks, and crowbars. Slashing knives, swords, tomahawks fixed to long handles, axes that resembled the headsman's axe of bygone days, and small cannon, were often preferred to the traditional weapons. The Lakeba people who met Cross and Cargill on the beach in October, 1835, carried muskets, spears, one club, a bayonet fixed to the end of a pole, bows, and bundles of arrows."

Archery

* Derrick 1950 p24

"Bows were useful alike in peace and war. They were six or seven feet long, and made from the pendent roots of the tiri or mangrove. Arrows were made from reeds, and were fitted with points of hard and polished wood."

* Archey 1967 p70

"Bows and arrows, short, round-headed throwing clubs (ula), and long, wooden spears with splendidly-rendered decorative barbs, were also part of the Fijians' arms and equipment."

Clubs (CulaCula, DromuDromu, GuGu, I Ula, Sali, Totokia, Vonotabua)

* Archey 1967 p70

"Few people had as heavy or as finely-carved clubs as the Fijians, and their variety and unusual shapes are always of interest particularly if one endeavours to ascertain their origin or derivation. The formally designed clubs derived from natural root-stocks are easy to identify; but careful study has been required to trace such characteristic forms as the 'pineapple' club and the 'lotus' club back to their stone-head club origin."

* The Bowers Blog online 2017-09-14 > Fijian kiakavo dance clubs

"Up until and in the few decades followings Fiji’s willing cessation to the United Kingdom in 1874, clubs were held as ferocious and vitally important weapons within a Fijian society which revolved in part around combat. Bows, arrows, and spears abounded in skirmishes between Fijian moieties, but even so the comparative prevalence of clubs is astonishing. In the 19th Century alone it is estimated that over 100,000 clubs may have been made in Fiji, 4,000 of which are now catalogued in museum collections around the world. Early explorers explain that even in peacetime Fijian men did not leave their homes without at least a decorative club, that visiting a neighboring village without a club was seen as discourteous, and that lowering a club was a standard sign of greeting throughout the Fijian Islands."

* Meyer 1995 v2 p458

"War clubs feature at the forefront of collections of Fijian art. As art forms, Fijian weapons stand alone in their sculptural purity. Each type of club had a predefined function and method of use. Club-making was a most prestigious art and some weapons took years to complete. The mana acquired by the weapon was shared equally between user and maker. Fire-arms, mostly American, .69' caliber flintlock muskets, were beautifully inlaid with whale-ivory and glass trade beads in the same manner as prized clubs."

* Metropolitan Museum of Art > Oceania

"Fijian Clubs In the past, warfare was central to many aspects of Fijian art and culture. Much of a man's social standing was determined by his prowess as a warrior. The most prestigious Fijian weapons were clubs. To slay an enemy with a club brought more honor than any other form of combat, earning a warrior the coveted status of koroi (killer). Clubs were made in a variety of forms, which were designed for specific purposes such as breaking limbs or delivering a crushing blow to the head.

* Paraísos perdidos 2007 p32-33

"La producción de mazas consiguió un desarrollo máximo en las islas Fiji cuya industria obtuvo las más bellas formas y los más altos cánones estilísticos. La elaboración era tan específica que puede decirse que se diseñaban para acciones concretas, teniendo en cuenta para quién iban destinadas, ya que estaban realizadas en maderas duras. La diferencia formal con respecto a las mazas de los otros dos archipiélagos estriba en la terminación de su talón y es precisamente por esta caracteristica por la que se intentado su clacificación: en Fiji es plana, sin ninguna protuberancia ni orificio para el engarce. ...

* Derrick 1950 p24

"[O]f all weapons the club was the favourite and the most prized. Having only crude tools, the craftsmen developed a high degree of skill and patience in making clubs fit for chiefs to wield. Some of these were wide, and bladed like an oar or a battleaxe; others were fashioned from the butts of uprooted trees; some were like heavy batons, plain and useful; others again were short and knobby, for throwing. The more ambitious designs included the 'pineapple' clubs, whose beaked ends were designed for pecking at an opponent's skull, and clubs shaped and moulded for months in the living tree."

* Meyer 1995 v2 p462

"The initiation of young men first involved the killing of a victim, often an unsuspecting and unarmed person. The young boy purchased a club from a specialist or cut one from a suitable tree. In the first part of the initiation ceremony the boy gave up his first club, was circumcised, lost his first name, and ritually killed a captured victim. In the second part of the ceremony, the boys were met by older warriors bearing powerful clubs. These weapons were passed back and forth from the men to the boys so that the youngsters could acquire the mana both of the weapons and the older warriors. The boys then spent four complete days and nights facing the ocean with their new clubs on their shoulders."

Spear

* Derrick 1950 p24

"The spears were from ten to fifteen feet long, and heavy, pronged, barbed, or armed with the sting of the ray. The best of them were richly carved."

* Ewins 1982 p48

"

Costume

* Derrick 1950 p20

"The Fijians' dress was scanty, but many took great care with it and showed pride in personal adornment. Cloth was made from the inner bark of the masi or paper mulberry tree, which grows to about ten feet in height, with a stem about one inch in diameter. When the tree was mature it was cut down, and peeled. The outer green skin was removed from the bark, and the inner layers were steeped in water and scraped, beaten with mallets on a slab, and either made into cloth immediately or left to be dried in the sun. The texture of the cloth varied from that of the thin gauze-like turbans worn by chiefs to that of heavy pieces built up of several thicknesses of bark and used for screens or partitions. Left in its natural white colour, the cloth was known as masi; usually, however, it was decorated by stencilling [sic] and painting in straight-line patterns or simple geometrical designs, or coloured by exposure to smoke."

* Geary ed. 2006 p140 (William E Teel w/ Christraud M Geary and Stéphanie Xatart, "Catalogue" p36-151) (decribing a bark cloth, Fiji late 19th-early 20th century)

"The practice of making tapa -- a cloth produced from the inner bark stripped from mulberry trees (Brusonnetia papyrifera) -- occurs throughout Polynesia but is particularly highly developed among the Fijians, who call the cloth masi. Women soak, beat, and join the bark into sheets, often of enormous size. Then they paint or stamp it with motifs in natural pigments. Various designs and forms of tapa exist. ... Prominent men wear a profusion of masi on special occasions. Fijians also exchange the cloth ceremonially as one of their most valuable goods."

Jewelry

* D'Alleva 2010 p112

"Throughout Polynesia, ornaments made of rare and precious materials expressed the mana, prestige, and genealogical strength of the elite. In general, ivory and whale-tooth ornaments became more widespread as a form of elite adornment in the nineteenth century as a result of trade with whaling ships and the introduction of metal tools. In Fiji, ivory and shell breastplates, civavonovono, were a sign of high status. The artists who made these breastplates were Tongans who had settled in Fiji."

* Waterhouse 1997 p220 (writing in 1866)

"The teeth of the devoured victims are made into necklaces, the thigh-bones are formed into needles for the purpose of sewing sail-mats, and the skull and other bones are hung in trees. There have been cases in which the skull has been used as a drinking-cup. The tobe (ornamental tuft of long hair) is frequently preserved as a memento and worn in the girdle of the conquering chief."

* Archey 1967 p70-71

"For further ornament the Fijian had chief recourse to pearl shell and to the teeth of the sperm whale. The breast-plate of pearl shell, covered with thin plates of whale ivory, were badges of chiefly rank, and possibly only men of some standing would have been able to acquire the handsome necklaces of slender ivory pendants wrought to a long, curved point and carefully matched for graduation in size.

"The undivided single whale tooth, or tambua was much more than an ornament; it was offered as a compliment between chiefs, and the presentation of a tambua was a necessary preliminary to the submission of a request for assistance or favour. In particular, it was presented with careful ceremony as a mark of homage to the ruler or overlord of a territorial federation. Not every official was entitled to be offered a tambua -- a lesser mark of respect was a gift of a portion of the dried root of the pepper tree, from which the kava drink was made."

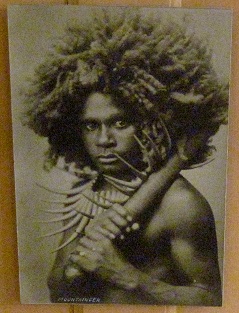

* Racinet 1988 p44

"A Vitien warrior, whose hair has been reddened either with lime water or the bark from a tree soaked in coconut oil, then curled back around the head and decorated with a comb of parrot feathers. He wears a collar of shells, pigs' teeth and rats' or bats' jaws."

Dish

* Legacy of collecting 2009 p110

"Dishes such as this (daveniyaqona) played an important role in pre-Christian ritual. They were used for the drinking of kava (yaqona, pronounced yanggona, in Fijian), a stimulant with medicinal properties which was a libation to the gods and was also drunk by priests when in trance as a result of being entered by an ancestral god. Kava was made from the roots and lower stems of a pepper plant (Piper methysticum) mixed with water. Research by Fergus Clunie has shown that there were two styles of kava drinking in Fiji in the early nineteenth century. One was the Tongan-influenced public ritual, which still takes place, in which chiefs were served with half-coconut cups from a large circular bowl (tanoa) with four or more legs. The other was the more private priestly ritual (burau), in which the god drank via the possessed priest. A shallow dish of this kind was filled with concentrated yaqona, which was then sucked up by the priest through a straw, thus allowing the liquid to pass directly into the god as a form of offering."

* Archey 1967 p71

"The drinking of kava, or yangona as the Fijians called it, was invested with solemn formality. 'Drinking in' was the essential part of the ceremony of installation of a chief, and a kava-drinking circle was the invariable form of deliberation in council or transaction of public business. The large wooden yangona bowl is placed before the chief, and the drink is prepared to the accompaniment of a ceremonial chant. The first cup is presented to the chief, those present steadily clapping during his libation, ceasing only when he spins the empty cup along the floor. Each member of the circle then receives his portion in turn, with the same jealous observance of precedence as in the apportionment and distribution of food at a feast."

* Ewins 1982 p51

"